Large language models, explained with a minimum of math and jargon

Want to really understand how large language models work? Here’s a gentle primer.

This is a copy of a post originally published over at Understanding AI, Timothy Lee’s excellent newsletter about recent progress in Artificial Intelligence. Tim’s a journalist with a master’s degree in computer science who also covers the economy for his other newsletter, Full Stack Economics.

This article was the result of a collaboration between the two of us. I learned a ton from working with Tim, who dove deep not only into the mechanics of how language models work, but also more recent research “probing” the function of different components and layers. Our goal was to write an explainer piece about how large language models work that goes beyond “they predict the next word” but doesn’t require extensive training in linear algebra or calculus. Hope you enjoy!

When ChatGPT was introduced last fall, it sent shockwaves through the technology industry and the larger world. Machine learning researchers had been experimenting with large language models (LLMs) for a few years by that point, but the general public had not been paying close attention and didn’t realize how powerful they had become.

Today almost everyone has heard about LLMs, and tens of millions of people have tried them out. But, still, not very many people understand how they work.

If you know anything about this subject, you’ve probably heard that LLMs are trained to “predict the next word,” and that they require huge amounts of text to do this. But that tends to be where the explanation stops. The details of how they predict the next word is often treated as a deep mystery.

One reason for this is the unusual way these systems were developed. Conventional software is created by human programmers who give computers explicit, step-by-step instructions. In contrast, ChatGPT is built on a neural network that was trained using billions of words of ordinary language.

As a result, no one on Earth fully understands the inner workings of LLMs. Researchers are working to gain a better understanding, but this is a slow process that will take years—perhaps decades—to complete.

Still, there’s a lot that experts do understand about how these systems work. The goal of this article is to make a lot of this knowledge accessible to a broad audience. We’ll aim to explain what’s known about the inner workings of these models without resorting to technical jargon or advanced math.

We’ll start by explaining word vectors, the surprising way language models represent and reason about language. Then we’ll dive deep into the transformer, the basic building block for systems like ChatGPT. Finally, we’ll explain how these models are trained and explore why good performance requires such phenomenally large quantities of data.

Word vectors

To understand how language models work, you first need to understand how they represent words. Human beings represent English words with a sequence of letters, like C-A-T for cat. Language models use a long list of numbers called a word vector. For example, here’s one way to represent cat as a vector:

[0.0074, 0.0030, -0.0105, 0.0742, 0.0765, -0.0011, 0.0265, 0.0106, 0.0191, 0.0038, -0.0468, -0.0212, 0.0091, 0.0030, -0.0563, -0.0396, -0.0998, -0.0796, …, 0.0002]

(The full vector is 300 numbers long—to see it all click here and then click “show the raw vector.”)

Why use such a baroque notation? Here’s an analogy. Washington DC is located at 38.9 degrees North and 77 degrees West. We can represent this using a vector notation:

Washington DC is at [38.9, 77]

New York is at [40.7, 74]

London is at [51.5, 0.1]

Paris is at [48.9, -2.4]

This is useful for reasoning about spatial relationships. You can tell New York is close to Washington DC because 38.9 is close to 40.7 and 77 is close to 74. By the same token, Paris is close to London. But Paris is far from Washington DC.

Language models take a similar approach: each word vector1 represents a point in an imaginary “word space,” and words with more similar meanings are placed closer together. For example, the words closest to cat in vector space include dog, kitten, and pet. A key advantage of representing words with vectors of real numbers(as opposed to a string of letters, like “C-A-T”) is that numbers enable operations that letters don’t.

Words are too complex to represent in only two dimensions, so language models use vector spaces with hundreds or even thousands of dimensions. The human mind can’t envision a space with that many dimensions, but computers are perfectly capable of reasoning about them and producing useful results.

Researchers have been experimenting with word vectors for decades, but the concept really took off when Google announced its word2vec project in 2013. Google analyzed millions of documents harvested from Google News to figure out which words tend to appear in similar sentences. Over time, a neural network trained to predict which words co-occur with which other words learned to place similar words (like dog and cat) close together in vector space.

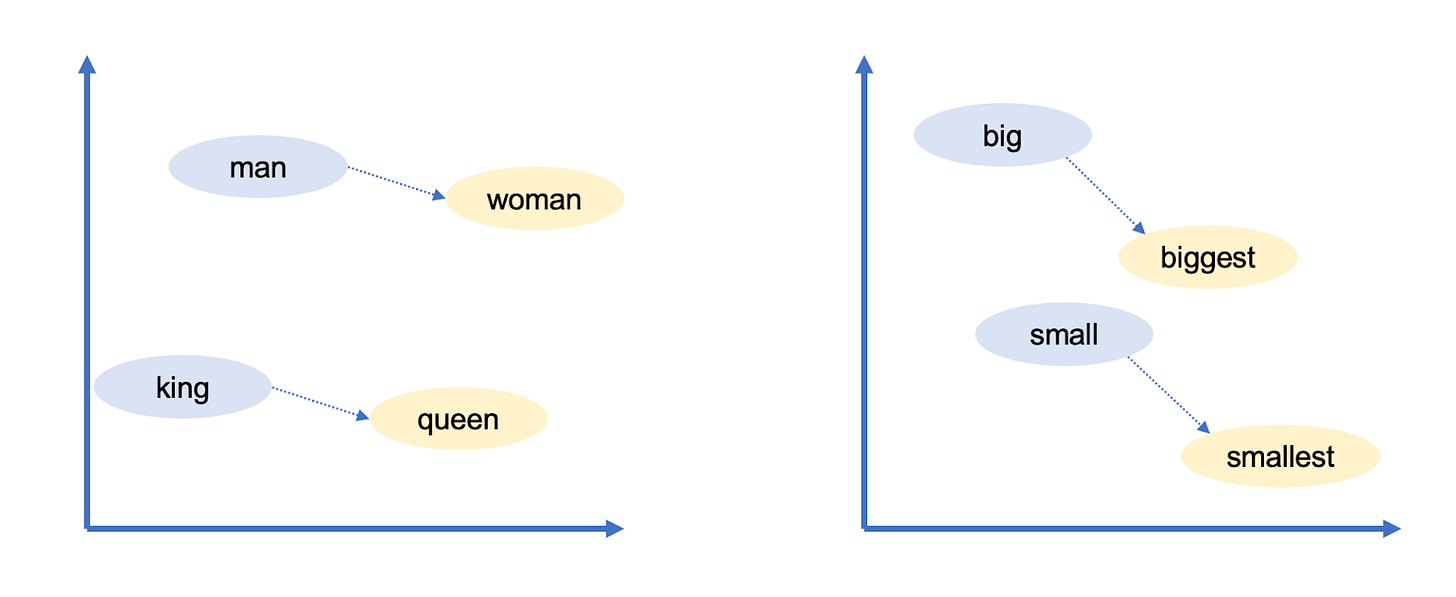

Google’s word vectors had another intriguing property: you could “reason” about words using vector arithmetic. For example, Google researchers took the vector for biggest, subtracted big, and added small. The word closest to the resulting vector was smallest.

You can use vector arithmetic to draw analogies! In this case big is to biggest as small is to smallest. Google’s word vectors captured a lot of other relationships:

Swiss is to Switzerland as Cambodian is to Cambodia. (nationalities)

Paris is to France as Berlin is to Germany. (capitals)

Unethical is to ethical as possibly is to impossibly. (opposites)

Mouse is to mice as dollar is to dollars. (plurals)

Man is to woman as king is to queen. (gender roles)

Because these vectors are built from the way humans use words, they end up reflecting many of the biases that are present in human language. For example, in some word vector models, doctor minus man plus woman yields nurse. Mitigating biases like this is an area of active research.

Nevertheless, word vectors are a useful building block for language models because they encode subtle but important information about the relationships between words. If a language model learns something about a cat (for example: it sometimes goes to the vet), the same thing is likely to be true of a kitten or a dog. If a model learns something about the relationship between Paris and France (for example: they share a language) there’s a good chance that the same will be true for Berlin and Germany and for Rome and Italy.

Word meaning depends on context

A simple word vector scheme like this doesn’t capture an important fact about natural language: words often have multiple meanings.

For example, the word bank can refer to a financial institution or to the land next to a river. Or consider the following sentences:

John picks up a magazine.

Susan works for a magazine.

The meanings of magazine in these sentences are related but subtly different. John picks up a physical magazine, while Susan works for an organization that publishes physical magazines.

When a word has two unrelated meanings, as with bank, linguists call them homonyms. When a word has two closely related meanings, as with magazine, linguists call it polysemy.

LLMs like ChatGPT are able to represent the same word with different vectors depending on the context in which that word appears. There’s a vector for bank (financial institution) and a different vector for bank (of a river). There’s a vector for magazine (physical publication) and another for magazine (organization). As you might expect, LLMs use more similar vectors for polysemous meanings than for homonymous meanings.

So far we haven’t said anything about how language models do this—we’ll get into that shortly. But we’re belaboring these vector representations because it’s fundamental to understanding how language models work.

Traditional software is designed to operate on data that’s unambiguous. If you ask a computer to compute “2 + 3,” there’s no ambiguity about what 2, +, or 3 mean. But natural language is full of ambiguities that go beyond homonyms and polysemy:

In “the customer asked the mechanic to fix his car” does his refer to the customer or the mechanic?

In “the professor urged the student to do her homework” does her refer to the professor or the student?

In “fruit flies like a banana” is flies a verb (referring to fruit soaring across the sky) or a noun (referring to banana-loving insects)?

People resolve ambiguities like this based on context, but there are no simple or deterministic rules for doing this. Rather, it requires understanding facts about the world. You need to know that mechanics typically fix customers’ cars, that students typically do their own homework, and that fruit typically doesn’t fly.

Word vectors provide a flexible way for language models to represent each word’s precise meaning in the context of a particular passage. Now let’s look at how they do that.

Transforming word vectors into word predictions

GPT-3, the model behind the original version of ChatGPT2, is organized into dozens of layers. Each layer takes a sequence of vectors as inputs—one vector for each word in the input text—and adds information to help clarify the meaning of that word and better predict which word might come next.

Let’s start by looking at a stylized example:

Each layer of an LLM is a transformer, a neural network architecture that was first introduced by Google in a landmark 2017 paper.

The model’s input, shown at the bottom of the diagram, is the partial sentence “John wants his bank to cash the.” These words, represented as word2vec-style vectors, are fed into the first transformer.

The transformer figures out that wants and cash are both verbs (both words can also be nouns). We’ve represented this added context as red text in parentheses, but in reality the model would store it by modifying the word vectors in ways that are difficult for humans to interpret. These new vectors, known as a hidden state, are passed to the next transformer in the stack.

The second transformer adds two other bits of context: it clarifies that bank refers to a financial institution rather than a river bank, and that his is a pronoun that refers to John. The second transformer produces another set of hidden state vectors that reflect everything the model has learned up to that point.

The above diagram depicts a purely hypothetical LLM, so don’t take the details too seriously. We’ll take a look at research into real language models shortly. Real LLMs tend to have a lot more than two layers. The most powerful version of GPT-3, for example, has 96 layers.

Research suggests that the first few layers focus on understanding the syntax of the sentence and resolving ambiguities like we’ve shown above. Later layers (which we’re not showing to keep the diagram a manageable size) work to develop a high-level understanding of the passage as a whole.

For example, as an LLM “reads through” a short story, it appears to keep track of a variety of information about the story’s characters: sex and age, relationships with other characters, past and current location, personalities and goals, and so forth.

Researchers don’t understand exactly how LLMs keep track of this information, but logically speaking the model must be doing it by modifying the hidden state vectors as they get passed from one layer to the next. It helps that in modern LLMs, these vectors are extremely large.

For example, the most powerful version of GPT-3 uses word vectors with 12,288 dimensions—that is, each word is represented by a list of 12,288 numbers. That’s 20 times larger than Google’s 2013 word2vec scheme. You can think of all those extra dimensions as a kind of “scratch space” that GPT-3 can use to write notes to itself about the context of each word. Notes made by earlier layers can be read and modified by later layers, allowing the model to gradually sharpen its understanding of the passage as a whole.

So suppose we changed our diagram above to depict a 96-layer language model interpreting a 1,000-word story. The 60th layer might include a vector for John with a parenthetical comment like “(main character, male, married to Cheryl, cousin of Donald, from Minnesota, currently in Boise, trying to find his missing wallet).” Again, all of these facts (and probably a lot more) would somehow be encoded as a list of 12,288 numbers corresponding to the word John. Or perhaps some of this information might be encoded in the 12,288-dimensional vectors for Cheryl, Donald, Boise, wallet, or other words in the story.

The goal is for the 96th and final layer of the network to output a hidden state for the final word that includes all of the information necessary to predict the next word.

Can I have your attention please

Now let’s talk about what happens inside each transformer. The transformer has a two-step process for updating the hidden state for each word of the input passage:

In the attention step, words “look around” for other words that have relevant context and share information with one another.

In the feed-forward step, each word “thinks about” information gathered in previous attention steps and tries to predict the next word.

Of course it’s the network, not the individual words, that performs these steps. But we’re phrasing things this way to emphasize that transformers treat words, rather than entire sentences or passages, as the basic unit of analysis. This approach enables LLMs to take full advantage of the massive parallel processing power of modern GPU chips. And it also helps LLMs to scale to passages with thousands of words. These are both areas where earlier language models struggled.

You can think of the attention mechanism as a matchmaking service for words. Each word makes a checklist (called a query vector) describing the characteristics of words it is looking for. Each word also makes a checklist (called a key vector) describing its own characteristics. The network compares each key vector to each query vector (by computing a dot product) to find the words that are the best match. Once it finds a match, it transfers information from the word that produced the key vector to the word that produced the query vector.

For example, in the previous section we showed a hypothetical transformer figuring out that in the partial sentence “John wants his bank to cash the,” his refers to John. Here’s what that might look like under the hood. The query vector for his might effectively say “I’m seeking: a noun describing a male person.” The key vector for John might effectively say “I am: a noun describing a male person.” The network would detect that these two vectors match and move information about the vector for John into the vector for his.

Each attention layer has several “attention heads,” which means that this information-swapping process happens several times (in parallel) at each layer. Each attention head focuses on a different task:

One attention head might match pronouns with nouns, as we discussed above.

Another attention head might work on resolving the meaning of homonyms like bank.

A third attention head might link together two-word phrases like “Joe Biden.”

And so forth.

Attention heads frequently operate in sequence, with the results of an attention operation in one layer becoming an input for an attention head in a subsequent layer. Indeed, each of the tasks we just listed above could easily require several attention heads rather than just one.

The largest version of GPT-3 has 96 layers with 96 attention heads each, so GPT-3 performs 9,216 attention operations each time it predicts a new word.

A real-world example

In the last two sections we presented a stylized version of how attention heads work. Now let’s look at research on the inner workings of a real language model. Last year scientists at Redwood Research studied how GPT-2, a predecessor to ChatGPT, predicted the next word for the passage “When Mary and John went to the store, John gave a drink to.”

GPT-2 predicted that the next word was Mary. The researchers found that three types of attention heads contributed to this prediction:

Three heads they called Name Mover Heads copied information from the Mary vector to the final input vector (for the word to). GPT-2 uses the information in this rightmost vector to predict the next word.

How did the network decide Mary was the right word to copy? Working backwards through GPT-2’s computational process, the scientists found a group of four attention heads they called Subject Inhibition Heads that marked the second John vector in a way that blocked the Name Mover Heads from copying the name John.

How did the Subject Inhibition Heads know John shouldn’t be copied? Working further backwards, the team found two attention heads they called Duplicate Token Heads. They marked the second John vector as a duplicate of the first John vector, which helped the Subject Inhibition Heads to decide that John shouldn’t be copied.

In short, these nine attention heads enabled GPT-2 to figure out that “John gave a drink to John” doesn’t make sense and choose “John gave a drink to Mary” instead.

We love this example because it illustrates just how difficult it will be to fully understand LLMs. The five-member Redwood team published a 25-page paper explaining how they identified and validated these attention heads. Yet even after they did all that work, we are still far from having a comprehensive explanation for why GPT-2 decided to predict Mary as the next word.

For example, how did the model know the next word should be someone’s name and not some other kind of word? It’s easy to think of similar sentences where Mary wouldn’t be a good next-word prediction. For example, in the sentence “when Mary and John went to the restaurant, John gave his keys to,” the logical next words would be “the valet.”

Presumably, with enough research computer scientists could uncover and explain additional steps in GPT-2’s reasoning process. Eventually, they might be able to develop a comprehensive understanding of how GPT-2 decided that Mary is the most likely next word for this sentence. But it could take months or even years of additional effort just to understand the prediction of a single word.

The language models underlying ChatGPT—GPT-3.5 and GPT-4—are significantly larger and more complex than GPT-2. They are capable of more complex reasoning than the simple sentence-completion task the Redwood team studied. So fully explaining how these systems work is going to be a huge project that humanity is unlikely to complete any time soon.

The feed-forward step

After the attention heads transfer information between word vectors, there’s a feed-forward network3 that “thinks about” each word vector and tries to predict the next word. No information is exchanged between words at this stage: the feed-forward layer analyzes each word in isolation. However, the feed-forward layer does have access to any information that was previously copied by an attention head. Here’s the structure of the feed-forward layer in the largest version of GPT-3:

The green and purple circles are neurons: mathematical functions that compute a weighted sum of their inputs.4

What makes the feed-forward layer powerful is its huge number of connections. We’ve drawn this network with three neurons in the output layer and six neurons in the hidden layer, but the feed-forward layers of GPT-3 are much larger: 12,288 neurons in the output layer (corresponding to the model’s 12,288-dimensional word vectors) and 49,152 neurons in the hidden layer.

So in the largest version of GPT-3, there are 49,152 neurons in the hidden layer with 12,288 inputs (and hence 12,288 weight parameters) for each neuron. And there are 12,288 output neurons with 49,152 input values (and hence 49,152 weight parameters) for each neuron. This means that each feed-forward layer has 49,152 * 12,288 + 12,288 * 49,152 = 1.2 billion weight parameters. And there are 96 feed-forward layers, for a total of 1.2 billion * 96 = 116 billion parameters! This accounts for almost two-thirds of GPT-3’s overall total of 175 billion parameters.

In a 2020 paper, researchers from Tel Aviv University found that feed-forward layers work by pattern matching: each neuron in the hidden layer matches a specific pattern in the input text. Here are some of the patterns that were matched by neurons in a 16-layer version of GPT-2:

A neuron in layer 1 matched sequences of words ending with “substitutes.”

A neuron in layer 6 matched sequences related to the military and ending with “base” or “bases.”

A neuron in layer 13 matched sequences ending with a time range such as “between 3 pm and 7” or “from 7:00 pm Friday until.”

A neuron in layer 16 matched sequences related to television shows such as “the original NBC daytime version, archived” or “time shifting viewing added 57 percent to the episode’s.”

As you can see, patterns got more abstract in the later layers. The early layers tended to match specific words, whereas later layers matched phrases that fell into broader semantic categories such as television shows or time intervals.

This is interesting because, as mentioned previously, the feed-forward layer examines only one word at a time. So when it classifies the sequence “the original NBC daytime version, archived” as related to television, it only has access to the vector for archived, not words like NBC or daytime. Presumably, the feed-forward layer can tell that archived is part of a television-related sequence because attention heads previously moved contextual information into the archived vector.

When a neuron matches one of these patterns, it adds information to the word vector. While this information isn’t always easy to interpret, in many cases you can think of it as a tentative prediction about the next word.

Feed-forward networks reason with vector math

Recent research from Brown University revealed an elegant example of how feed-forward layers help to predict the next word. Earlier we discussed Google’s word2vec research showing it was possible to use vector arithmetic to reason by analogy. For example, Berlin - Germany + France = Paris.

The Brown researchers found that feed-forward layers sometimes use this exact method to predict the next word. For example, they examined how GPT-2 responded to the following prompt: “Q: What is the capital of France? A: Paris Q: What is the capital of Poland? A:”

The team studied a version of GPT-2 with 24 layers. After each layer, the Brown scientists probed the model to observe its best guess at the next token. For the first 15 layers, the top guess was a seemingly random word. Between the 16th and 19th layer, the model started predicting that the next word would be Poland—not correct, but getting warmer. Then at the 20th layer, the top guess changed to Warsaw—the correct answer—and stayed that way in the last four layers.

The Brown researchers found that the 20th feed-forward layer converted Poland to Warsaw by adding a vector that maps country vectors to their corresponding capitals. Adding the same vector to China produced Beijing.

Feed-forward layers in the same model used vector arithmetic to transform lower-case words into upper-case words and present-tense words into their past-tense equivalents.

The attention and feed-forward layers have different jobs

So far we’ve looked at two real-world examples of GPT-2 word predictions: attention heads helping to predict that John gave a drink to Mary, and a feed-forward layer helping to predict that Warsaw was the capital of Poland.

In the first case, Mary came from the user-provided prompt. But in the second case, Warsaw wasn’t in the prompt. Rather GPT-2 had to “remember” the fact that Warsaw was the capital of Poland—information it learned from training data.

When the Brown researchers disabled the feed-forward layer that converted Poland to Warsaw, the model no longer predicted Warsaw as the next word. But interestingly, if they then added the sentence “The capital of Poland is Warsaw” to the beginning of the prompt, then GPT-2 could answer the question again. This is probably because GPT-2 used attention heads to copy the name Warsaw from earlier in the prompt.

This division of labor holds more generally: attention heads retrieve information from earlier words in a prompt, whereas feed-forward layers enable language models to “remember” information that’s not in the prompt.

Indeed, one way to think about the feed-forward layers is as a database of information the model has learned from its training data. The earlier feed-forward layers are more likely to encode simple facts related to specific words, such as “Trump often comes after Donald.” Later layers encode more complex relationships like “add this vector to convert a country to its capital.”

How language models are trained

Many early machine learning algorithms required training examples to be hand-labeled by human beings. For example, training data might have been photos of dogs or cats with a human-supplied label (“dog” or “cat”) for each photo. The need for humans to label data made it difficult and expensive to create large enough data sets to train powerful models.

A key innovation of LLMs is that they don’t need explicitly labeled data. Instead, they learn by trying to predict the next word in ordinary passages of text. Almost any written material—from Wikipedia pages to news articles to computer code—is suitable for training these models.

For example, an LLM might be given the input “I like my coffee with cream and” and be supposed to predict “sugar” as the next word. A newly-initialized language model will be really bad at this because each of its weight parameters—175 billion of them in the most powerful version of GPT-3—will start off as an essentially random number.

But as the model sees many more examples—hundreds of billions of words—those weights are gradually adjusted to make better and better predictions.

Here’s an analogy to illustrate how this works. Suppose you’re going to take a shower, and you want the temperature to be just right: not too hot, and not too cold. You’ve never used this faucet before, so you point the knob to a random direction and feel the temperature of the water. If it’s too hot, you turn it one way; if it’s too cold, you turn it the other way. The closer you get to the right temperature, the smaller the adjustments you make.

Now let’s make a couple of changes to the analogy. First, imagine that there are 50,257 faucets instead of just one. Each faucet corresponds to a different word like the, cat, or bank. Your goal is to have water only come out of the faucet corresponding to the next word in a sequence.

Second, there’s a maze of interconnected pipes behind the faucets, and these pipes have a bunch of valves on them as well. So if water comes out of the wrong faucet, you don’t just adjust the knob at the faucet. You dispatch an army of intelligent squirrels to trace each pipe backwards and adjust each valve they find along the way.

This gets complicated because the same pipe often feeds into multiple faucets. So it takes careful thought to figure out which valves to tighten and which ones to loosen, and by how much.

Obviously, this example quickly gets silly if you take it too literally. It wouldn’t be realistic or useful to build a network of pipes with 175 billion valves. But thanks to Moore’s Law, computers can and do operate at this kind of scale.

All the parts of LLMs we’ve discussed in this article so far—the neurons in the feed-forward layers and the attention heads that move contextual information between words—are implemented as a chain of simple mathematical functions (mostly matrix multiplications) whose behavior is determined by adjustable weight parameters. Just as the squirrels in my story loosen and tighten the valves to control the flow of water, so the training algorithm increases or decreases the language model’s weight parameters to control how information flows through the neural network.

The training process happens in two steps. First there’s a “forward pass,” where the water is turned on and you check if it comes out the right faucet. Then the water is turned off and there’s a “backwards pass” where the squirrels race along each pipe tightening and loosening valves. In digital neural networks, the role of the squirrels is played by an algorithm called backpropagation, which “walks backwards” through the network, using calculus to estimate how much to change each weight parameter.5

Completing this process—doing a forward pass with one example and then a backwards pass to improve the network’s performance on that example—requires hundreds of billions of mathematical operations. And training a model as big as GPT-3 requires repeating the process billions of times—once for each word of training data.6

OpenAI estimates that it took more than 300 billiontrillionfloating point calculations to train GPT-3—that’s months of work for dozens of high-end computer chips.

The surprising performance of GPT-3

You might find it surprising that the training process works as well as it does. ChatGPT can perform all sorts of complex tasks—composing essays, drawing analogies, and even writing computer code. So how does such a simple learning mechanism produce such a powerful model?

One reason is scale. It’s hard to overstate the sheer number of examples that a model like GPT-3 sees. GPT-3 was trained on a corpus of approximately 500 billion words. For comparison a typical human child encounters roughly 100 million words by age 10.

Over the last five years, OpenAI has steadily increased the size of its language models. In a widely-read 2020 paper, OpenAI reported that the accuracy of its language models scaled “as a power-law with model size, dataset size, and the amount of compute used for training, with some trends spanning more than seven orders of magnitude.”

The larger their models got, the better they were at tasks involving language. But this was only true if they increased the amount of training data by a similar factor. And to train larger models on more data, you need a lot more computing power.

OpenAI’s first LLM, GPT-1, was released in 2018. It used 768-dimensional word vectors and had 12 layers for a total of 117 million parameters. A few months later, OpenAI released GPT-2. Its largest version had 1,600-dimensional word vectors, 48 layers, and a total of 1.5 billion parameters.

In 2020, OpenAI released GPT-3, which featured 12,288-dimensional word vectors and 96 layers for a total of 175 billion parameters.

Finally, this year OpenAI released GPT-4. The company has not published any architectural details, but GPT-4 is widely believed to be significantly larger than GPT-3.

Each model not only learned more facts than its smaller predecessors, it also performed better on tasks requiring some form of abstract reasoning:

For example, consider the following story:

Here is a bag filled with popcorn. There is no chocolate in the bag. Yet, the label on the bag says “chocolate” and not “popcorn.” Sam finds the bag. She had never seen the bag before. She cannot see what is inside the bag. She reads the label.

You can probably guess that Sam believes the bag contains chocolate and will be surprised to discover popcorn inside. Psychologists call this capacity to reason about the mental states of other people “theory of mind.” Most people have this capacity from the time they’re in grade school. Experts disagree about whether any non-human animals (like chimpanzees) have theory of mind, but there’s general consensus that it is important for human social cognition.

Earlier this year, Stanford psychologist Michal Kosinski published research examining the ability of LLMs to solve theory-of-mind tasks. He gave various language models passages like the one we quoted above and then asked them to complete a sentence like “she believes that the bag is full of.” The correct answer is “chocolate,” but an unsophisticated language model might say “popcorn” or something else.

GPT-1 and GPT-2 flunked this test. But the first version of GPT-3, released in 2020, got it right almost 40 percent of the time—a level of performance Kosinski compares to a three-year-old. The latest version of GPT-3, released last November, improved this to around 90 percent—on par with a seven-year-old. GPT-4 answered about 95 percent of theory-of-mind questions correctly.

“Given that there is neither an indication that ToM-like ability was deliberately engineered into these models, nor research demonstrating that scientists know how to achieve that, ToM-like ability likely emerged spontaneously and autonomously, as a byproduct of models’ increasing language ability,” Kosinski wrote.

It’s worth noting that researchers don’t all agree that these results indicate evidence of Theory of Mind: for example, small changes to the false-belief task led to much worse performance by GPT-3; and GPT-3 exhibits more variable performance across other tasks measuring theory of mind. As one of us (Sean) has written, it could be that successful performance is attributable to confounds in the task—a kind of “clever Hans” effect, only in language models rather than horses.

Nonetheless, the near-human performance of GPT-3 on several tasks designed to measure theory of mind would have been unthinkable just a few years ago—and is consistent with the idea that bigger models are generally better at tasks requiring high-level reasoning.

This is just one of many examples of language models appearing to spontaneously develop high-level reasoning capabilities. In April, researchers at Microsoft published a paper arguing that GPT-4 showed early, tantalizing hints of artificial general intelligence—the ability to think in a sophisticated, human-like way.

For example, one researcher asked GPT-4 to draw a unicorn using an obscure graphics programming language called TiKZ. GPT-4 responded with a few lines of code that the researcher then fed into the TiKZ software. The resulting images were crude, but they showed clear signs that GPT-4 had some understanding of what unicorns look like.

The researchers thought GPT-4 might have somehow memorized code for drawing a unicorn from its training data, so they gave it a follow-up challenge: they altered the unicorn code to remove the horn and move some of the other body parts. Then they asked GPT-4 to put the horn back on. GPT-4 responded by putting the horn in the right spot:

GPT-4 was able to do this even though the training data for the version tested by the authors was entirely text-based. That is, there were no images in its training set. But GPT-4 apparently learned to reason about the shape of a unicorn’s body after training on a huge amount of written text.

At the moment, we don’t have any real insight into how LLMs accomplish feats like this. Some people argue that examples like this demonstrate that the models are starting to truly understand the meanings of the words in their training set. Others insist that language models are “stochastic parrots” that merely repeat increasingly complex word sequences without truly understanding them.

This debate points to a deep philosophical tension that may be impossible to resolve. Nonetheless, we think it is important to focus on the empirical performance of models like GPT-3. If a language model is able to consistently get the right answer for a particular type of question, and if researchers are confident that they have controlled for confounds (e.g., ensuring that the language model was not exposed to those questions during training), then that is an interesting and important result whether or not it understands language in exactly the same sense that people do.

Another possible reason that training with next-token prediction works so well is that language itself is predictable. Regularities in language are often (though not always) connected to regularities in the physical world. So when a language model learns about relationships among words, it’s often implicitly learning about relationships in the world too.

Further, prediction may be foundational to biological intelligence as well as artificial intelligence. In the view of philosophers like Andy Clark, the human brain can be thought of as a “prediction machine”, whose primary job is to make predictions about our environment that can then be used to navigate that environment successfully. Intuitively, making good predictions benefits from good representations—you’re more likely to navigate successfully with an accurate map than an inaccurate one. The world is big and complex, and making predictions helps organisms efficiently orient and adapt to that complexity.

Traditionally, a major challenge for building language models was figuring out the most useful way of representing different words—especially because the meanings of many words depend heavily on context. The next-word prediction approach allows researchers to sidestep this thorny theoretical puzzle by turning it into an empirical problem. It turns out that if we provide enough data and computing power, language models end up learning a lot about how human language works simply by figuring out how to best predict the next word. The downside is that we wind up with systems whose inner workings we don’t fully understand.

Technically, LLMs operate on fragments of words called tokens, but we’re going to ignore this implementation detail to keep the article to a manageable length.

Technically, the original version of ChatGPT is based on GPT-3.5, a successor to GPT-3 that underwent a process called Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF). OpenAI hasn't released all the architectural details for this model, so in this piece we'll focus on GPT-3, the last version that OpenAI has described in detail.

The feed-forward network is also known as a multilayer perceptron. Computer scientists have been experimenting with this type of neural network since the 1960s.

Technically, after a neuron computes a weighted sum of its inputs, it passes the result to an activation function. We’re going to ignore this implementation detail, but you can read Tim’s 2018 explainer if you want a full explanation of how neurons work.

If you want to learn more about backpropagation, check out Tim’s 2018 explainer on how neural networks work.

In practice, training is often done in batches for the sake of computational efficiency. So the software might do the forward pass on 32,000 tokens before doing a backward pass.

Very nice article.

I recently had a discussion with Claude about its intelligence. You may find it interesting. (https://russabbott.substack.com/p/in-which-i-convince-an-llm-that-it)

h = x + self.attention.forward(

self.attention_norm(x), start_pos, freqs_cis, mask

)

out = h + self.feed_forward.forward(self.ffn_norm(h))

This is the transformer code of llama. I really don’t understand which part of this code has anything to do with neurons.

If you can help me answer it, I would be very grateful.