Calibrating expectations

The so-called "habitability problem" never really went away.

Early on in graduate school, I was interested in trust: specifically, the (normative) question of how much to trust new technologies enabled by machine learning (ML), and the (descriptive) question of which factors led individuals to trust or distrust these systems. One way to think about this is as a problem of calibration. From this perspective, users of a tool should be well-calibrated to what it can and can’t do, so that they make effective use of the tool but don’t deploy it in inappropriate settings—i.e., they should trust it “just the right amount”.

Notably, this was years before the advent of ChatGPT. At the time, research on trust focused on emerging tools like self-driving cars and “AI-assisted” decision-making technologies (e.g., for domains like healthcare). As a cognitive scientist, I was especially drawn to the question of whether and how designing these tools to appear more “human”—such as the use of a language interface—might influence human judgments about their capabilities or even the degree to which humans trusted them (whether that trust was appropriate or not).

My graduate research went in a different direction for a variety of reasons, one of which was that the language interfaces of the time were simply not particularly capable. But I’ve rekindled my interest in the topic in the last year or so, as large language models (LLMs)—or more accurately, LLM-equipped software tools—are deployed in more and more settings, despite a lack of consensus on how to properly evaluate these systems. Individuals thus struggle to calibrate their expectations: as Kelsey Piper wrote in a recent article for The Argument, the same system (e.g., Claude Code) might produce clever, functional code in a matter of minutes and generate infuriating, inexplicable errors.

I don’t think this problem is going away anytime soon, and I’m certainly not going to solve it in a single essay. But it is a longstanding problem in human-machine interaction, and as always, I think contextualizing the problem in that history can help us understand both the parallels and particularities of the current moment with respect to the past.

Language interfaces and the habitability problem

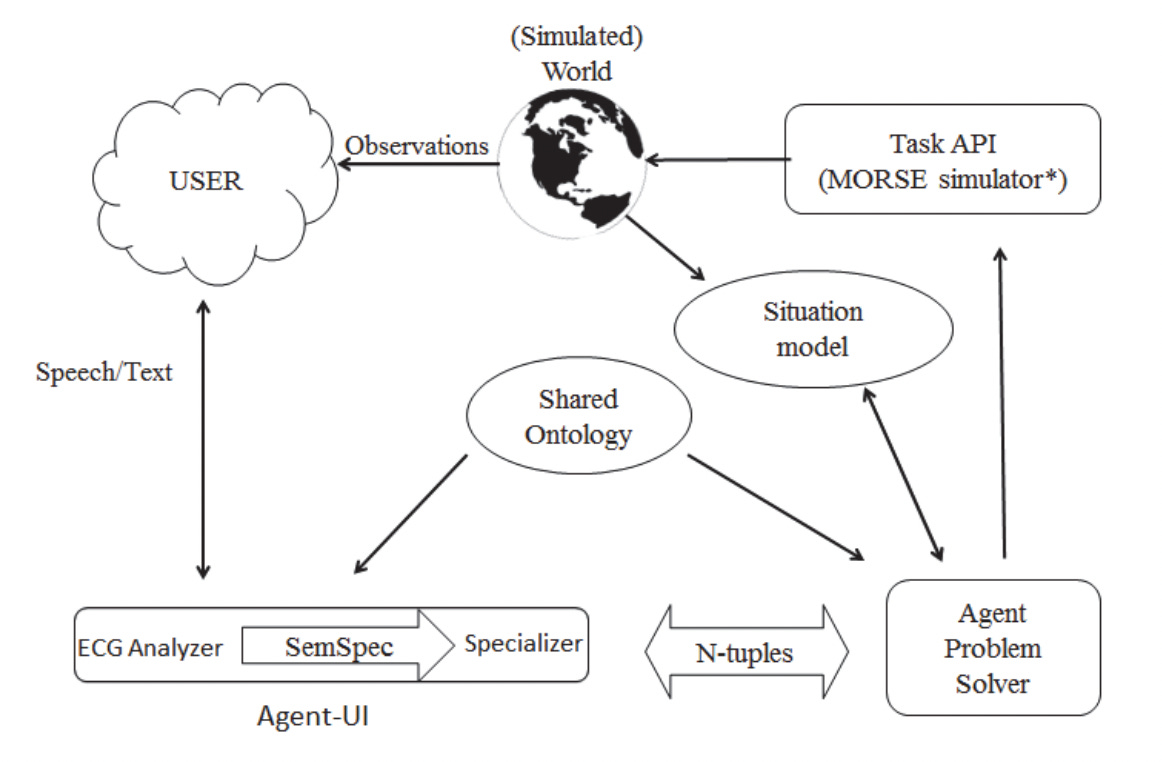

I’ll start with some more personal history: before I started graduate school, I worked for several years at a research institute in Berkeley called the International Computer Science Institute (ICSI). I worked in Jerry Feldman's research group on a project designing a natural language interface (NLI) for a simulated robotics application. These days, NLIs are commonplace—some have even argued text is the “universal” interface—but at the time, they were quite limited in scope and deployment.

The major bottleneck is, of course, that building a system that understands language is very hard! By “understand” language I don’t merely mean processing it (i.e., converting strings of text into some other representational format), but somehow producing an action in response to linguistic input—such as planning trips, controlling an operating system, or interacting with the world (or a simulation of the world) in some way, as in Terry Winograd’s famous SHRDLU.

The working assumption of much research (including our own) was that natural language understanding (or “NLU”) was an inherently domain-constrained problem: that is, while it might be possible (though difficult) to build end-to-end systems that mapped a limited set of linguistic commands to actions for specific applications, building a “general-purpose” language interface was hopelessly out-of-scope.

Part of the challenge with a “general-purpose” system is, obviously, that “general-purpose” includes quite a lot. For what it’s worth, that challenge is very much alive with current LLM-equipped software tools (as I discuss later on in this post).

But another challenge lay with what you might think of as the “front end” of these tools: the component responsible for processing linguistic input and converting it into a usable format for some downstream application. Human language is incredibly flexible—there are all sorts of ways one can say the same thing, or almost the same thing—and it’s very difficult to design, by hand, a system that can competently process all of this linguistic formulations.

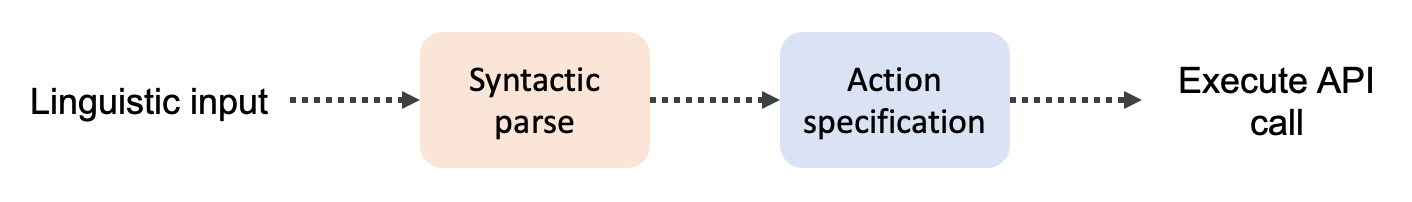

This is where the habitability problem comes in. Suppose you, a computational linguist, write a series of rules that can cover a variety of sentences; let’s call the set of these rules a “grammar”. This could mean different things to different people, but in short, I mean something like: convert a string like “Put the red block on the blue block” into some kind of syntactic parse. You’ve also written a component that converts this parse into some kind of usable action specification, e.g., move(moved_object(type = block, color=red), target_location(object(type = block, color = blue), relation = on)).1 Finally, you’ve written code that uses this action specification to actually make the relevant changes in the downstream application—in this case, perhaps making API calls to a simulated robotics application.

Now, such a system could fail in at least two obvious ways. First, our grammar might fail to identify a suitable syntactic parse, i.e., there is no grammatical rule that produces a complete analysis of the sentence. And second, even if we produce a syntactic analysis, our system for producing an action specification might not “know” what to do with that analysis—or which API calls to make. In both cases, the user of the system has produced a sentence that the system does not “understand” in the sense that no suitable output is produced.

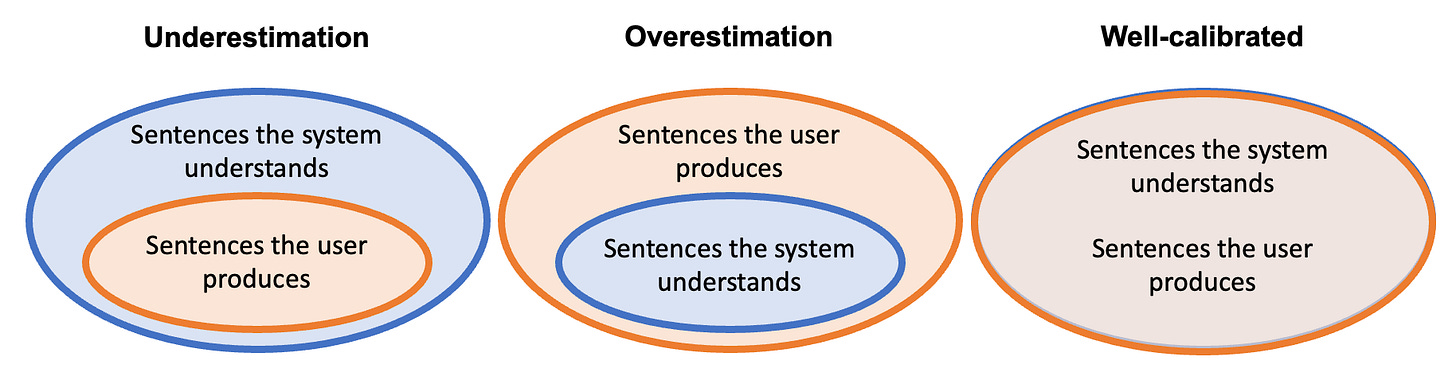

The failures above correspond to what we might think of as overestimation: the user has produced a command under the impression that the system will be able to execute it, but the system is unable to do so. Yet another, more subtle failure mode corresponds to underestimation: that is, a user fails to fully exploit the range of linguistic formulations and actions available to them. To make this concrete: the system might be able to execute commands like “Put the red block on the blue block”, but for whatever reason, the user doesn’t think of this as the type of thing the system can do—so they never ask.

These two failure modes are the twin sides of the habitability problem, as originally defined by Watt (1968):

A “habitable” language is one in which its users can express themselves without straying over the language’s boundaries into unallowed sentences.

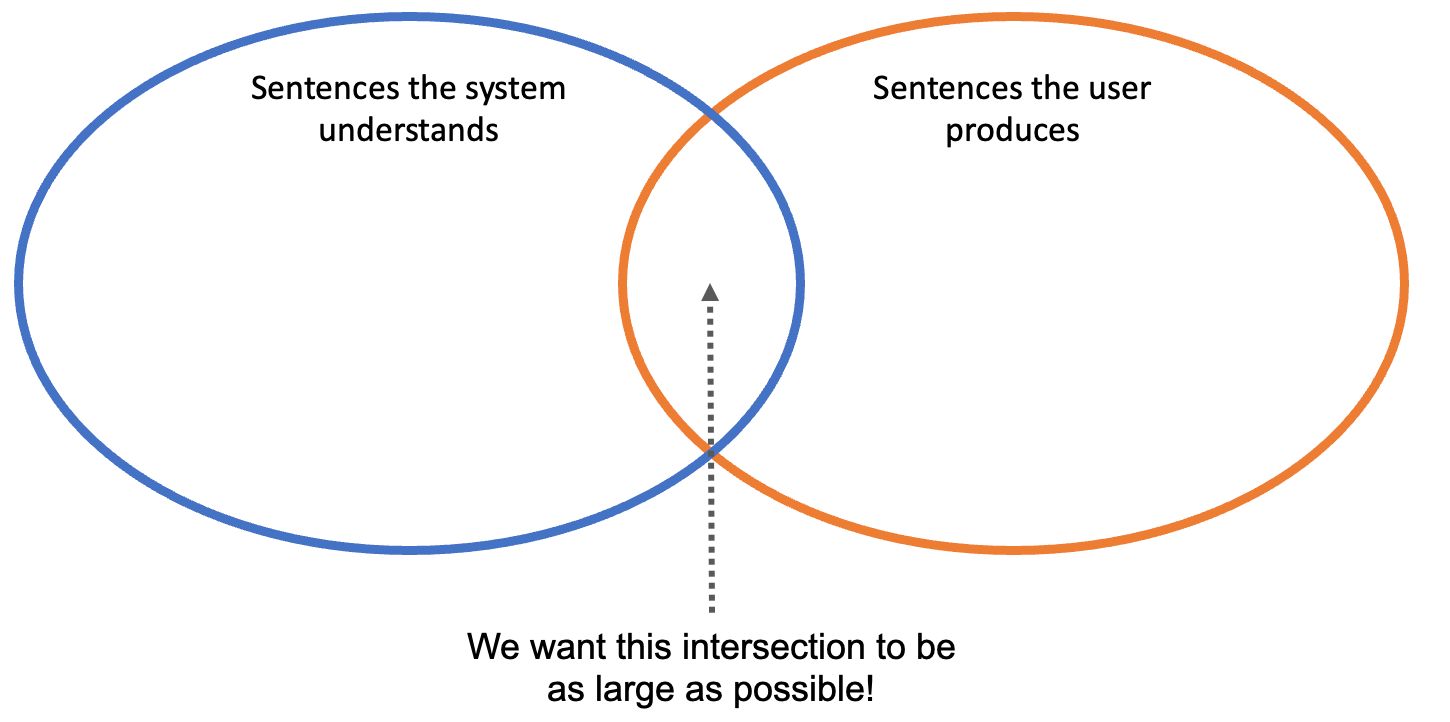

It might help to depict this problem visually. We can think of two “sets” of sentences: first, sentences the system understands (i.e., produces the correct action from linguistic input); and second, sentences the user produces (i.e., commands or “intended actions”). In the ideal case, these two sets should have complete overlap—everything the user produces should be comprehensible by the system, and everything the system can do is (at least in principle) accessible to the user. In other words, we want the intersection between these sets to be as large as possible.

Framing it this way allows us to flesh out what we mean by underestimation and overestimation. In this framework, underestimation occurs when the set of sentences a system understands is larger than the set of sentences the user produces; overestimation is when the set of sentences a user produces is larger than the set of sentences a system understands. Finally, appropriate calibration is when these sets are, effectively, identical.

For engineers building NLIs, then, the challenge becomes how to effectively “steer” users into using language that the system understands and away from using language that the system won’t understand. This is not an easy problem to solve, and approaches might include strategies as diverse as “wizard-of-oz” studies (in which they gather data about the kinds of language a person might use with such a system), instructional demos (in which the range of abilities and limitations of a system can be illustrated), and more indirect approaches (e.g., having the system use certain linguistic formulations to “prime” those same formulations in users).

The habitability problem was originally defined in the context of mostly symbolic, rule-based systems for processing natural language—an approach now sometimes called “good old-fashioned AI” (or “GOFAI”). The problem was also identified at a time when users interacted with computers through text-based interfaces; as others have pointed out, interest in the habitability problem waned as graphical user-interfaces (or “GUIs”) became more popular in the following decades, even though some researchers continued to develop language interfaces.2

With tools like ChatGPT, however, language interfaces are very much back—and it’s clear that the habitability problem, or at least a version of it, never really went away.

From GOFAI to LLMs

LLMs are an example of the so-called “connectionist” approach to AI, which is usually placed in contrast to symbolic, rule-based approaches. Specifically, LLMs are large neural networks trained to predict tokens (e.g., words) in the context of other tokens (e.g., a sentence). These systems can be fine-tuned and modified in all sorts of ways, such as using human feedback or training them to solve questions with objective answers (“verifiable rewards”); they can also be trained on other modalities, such as images or audio. Finally, such a model can be used as a component of a larger system, which I call “LLM-equipped software tools”.

But at their core, each underlying system is essentially the same:

Some input is presented to the model.

The model produces a probability distribution over subsequent tokens.

Some other process is used to sample from this probability distribution.

What’s surprising—and in many ways remarkable—about modern LLMs is that this relatively simple process, applied recursively to its own output, often produces coherent, contextually appropriate outputs. It’s worth noting that this is itself a nontrivial finding: for many years, neural networks trained on the statistics of language struggled to produce grammatical sentences—let alone semantically sensible ones. But training larger models on larger amounts of data seems to go a long way towards improving the grammaticality and sensibility of their outputs. Moreover, the various “post-training” techniques that have been applied to these systems have resulted in tools that solve difficult reasoning tasks and generate computer code.

I mention all this because I think it’s relevant to understanding the excitement over LLMs. As I noted in the previous section, there was always an understandable skepticism that an AI system composed of hand-written rules could ever be “general-purpose”. The set of possible English sentences—let alone desired actions—seemed too vast and too under-determined to build a system that could contend with all of them. By contrast, LLMs appear to be able to contend with a variety of linguistic formulations; they can also be trained to produce API calls to other system components (like a calculator). There’s a temptation, then, to hope that LLMs could, one day, serve as something like a “general-purpose” language interface—or, to use a more popular (though controversial) term, that they might one day represent something like “Artificial General Intelligence” (or “AGI”).

Now, I do think LLMs are quite interesting; that’s why I research them and write about them so often! But there’s a gap between: observing, first, that LLMs can learn, in some bottom-up way, statistical patterns that allow them to produce coherent language and computer code; and inferring, second, that they are (or will be) “general-purpose” language interfaces, i.e., that the habitability problem has somehow been circumvented. I think we should be very careful not to elide or minimize this gap.

It’s also notable, in my view, that even the strongest proponents of LLMs as general-purpose systems will often readily acknowledge that there are a number of “alignment problems” to solve. The term “alignment” signifies many different (related) concepts in the AI discourse, but one useful, straightforward definition refers simply to ensuring that a user’s intentions are in some sense aligned with the response of the system they’re using. This definition helpfully covers a variety of failure modes, from cases of obvious incompetence to more subtle misinterpretations. It also makes it clear that the problem of “alignment” shares many features with the habitability problem, or more generally with the problem of calibration.

Calibration is also about us

One thing I appreciate about the calibration perspective is that it makes it clear this is a two-way street. Building and validating a more capable system that correctly interprets a user’s requests is, of course, half the battle. But the other half concerns the human side. What kinds of mental models do people have about the abilities and limitations of LLMs? When do people underestimate or overestimate their abilities? And perhaps most crucially, how can we encourage the proper degree of calibration?

As I mentioned at the start of this post, I don’t know the answers to these questions—they are, to my mind, questions that require both empirical research and discussion of what our actual societal values are and should be. Part of the answer surely lies in educating individuals about how LLMs and related systems actually work. But I will close with several observations that I believe to be true about LLMs and calibration.

First, I suspect that one source of calibration difficulty arises from the fact that these systems are language interfaces in particular. Humans tend to associate the systematic, appropriate use of linguistic symbols with other cognitive abilities, or even emotions and an interior life. For some domains, those correlations might hold for LLMs as well, if only because the statistics of language contain a remarkable degree of information about the world and the way it works. At the same time, there will be many domains in which LLMs produce surprising, inexplicable failures—and our surprise at these failures should be viewed as a warning, in my view, that we don’t understand why or how these systems produce the behaviors they do.

That brings me to my second observation. With many tools, we know what it should and should not be used for; we have a general understanding of its affordances. We also know—or trust that someone, somewhere knows—why the tool works in this way. In many cases we even extrapolate this assumption to the mechanics of the world around us. This fundamental assumption underlies much of what sociologist Max Weber called “disenchantment”:

It is the knowledge or the conviction that if only we wished to understand them we could do so at any time. It means that in principle, then, we are not ruled by mysterious, unpredictable forces, but that, on the contrary, we can in principle control everything by means of calculation. That in turn means the disenchantment of the world. (pg. 12-13)

As I’ve argued before, this assumption of legibility starts to break down with non-deterministic, opaque systems like LLMs. While we certainly understand many low-level properties of LLMs (e.g., how they’re trained), we lack an understanding of which internal mechanisms produce the behaviors we observe—which is precisely why research on interpretability is so important.

More generally, this leads to a strange predicament in which a tool is available for use, but it’s not necessarily clear what we should use it for. It might be useful for a range of downstream applications, but it also might not be. This is, to me, one of the most aggravating facts about how many LLM products are marketed: customers pay some amount of money for access to a system with under-specified capacities; if they deploy that system in a context that’s inappropriate and it leads to failures, the company selling the product has some degree of plausible deniability—after all, the product specification never stated the model could be used in this exact circumstance; and perhaps it simply wasn’t prompted in the right way (i.e., “user error”).

One might imagine addressing this problem of under-specified capacities by developing and running benchmarks that evaluate those capacities. In theory, then, you could imagine paying more for a model (and deploying it more broadly) that performs better on more benchmarks than a model that performs poorly. But here, we run, as always, into the problem of construct validity: are these benchmarks actually measuring the capability we think they’re measuring? Is measuring something like “programming ability” (let alone “reasoning”) even a coherent goal? How exactly should we use the results of such a benchmark to guide actual decisions about safely, reliably deploying a model?

This is also why I often feel a deep sense about ambivalence when arguments about the capabilities of LLMs break out. On the one hand, I agree with articles like this one pointing out that it’s not necessarily appropriate to conflate the training objective of a model (e.g., predicting the next word) with the capabilities that model develops. At the same time, I continue to think there’s considerable uncertainty what those capabilities actually are—and I agree with Melanie Mitchell’s arguments here that we ought to exercise restraint in ascribing human-like cognitive capacities on the basis of an LLM’s behavior on tests designed for human participants. As I’ve written before, the same behavior can be produced by multiple mechanisms, and the same test may not necessarily “mean the same thing” for humans and LLMs.

Once again, I don’t have the answers. But my underlying ethos on this matter is one of epistemological caution. There is much we don’t know—perhaps much we can’t ever know—and I think it’s worth calibrating to that uncertainty.

With the caveat, of course, that this example is probably not well-designed in all sorts of ways.)

It’s also worth noting that a version of the habitability problem very much applies to GUIs as well!

Brilliant framing of how GOFAI's habitability issue never got solved, just got eclipsed by GUIs. I've been debugging LLM-based tools lately and its wild how much the overestimation problem shows up when non-technical users hit edge cases. What makes it trickier than older NLIs is the illusion of competence becuase the failures aren't consistent, which makes calibration way harder.

What a phenomenal essay. Gonna need to re-read this a few times to absorb the various puzzles you've presented!