Language models and the ineffable

The limits of our language-based benchmarks are the limits of our language.

Large language models (LLMs) trained on text alone1 update various weight matrices to enable them to better predict upcoming words. In doing so, they learn quite a bit about the structure of language, such as aspects of syntax and even semantics. Perhaps more surprisingly, they appear to learn about the world beyond language as well. In various psycholinguistic tasks, “vanilla” language models—i.e., those trained solely to predict the next word from large text corpora—display some sensitivity (albeit less than humans; more on this below) to the physical plausibility of events, discourse context, and even the implied belief states of characters in a passage.

For many researchers (including myself), these findings have been surprising. My expectation—informed by theories like embodied cognition—was that reasoning about the physical and social world required grounded experience in the physical and social world. For instance, if a person read a sentence like the following:

When the rock smashed into the vase, it broke.

…I assumed they drew upon their physical experience with rocks and vases to resolve the pronoun “it” to its likely antecedent. Yet some language models trained only on the distributional statistics of words respond in ways similar to how humans respond. Thus, one relatively straightforward interpretation is that the (qualified) success of text-based LLMs on these tasks suggests that many capacities can at least partially develop in the absence of grounded experience—i.e., that these things can be learned from the distributional statistics of language. It doesn’t, of course, entail that humans do things this way; nor does it necessarily entail that LLMs have developed a sophisticated “world model” (however that might be defined). But it serves as a proof-of-concept that some of the relevant behaviors we take to be reflective of world knowledge in humans could be produced by training on text alone.

To be clear, there are plenty of performance gaps between vanilla text-based LLMs and humans (including on the tasks I’ve mentioned, and many others) which proponents of grounded theories can point to as evidence that there’s something missing.2 And ultimately, my view is that theoretical arguments about what you can learn from language alone should hinge primarily on empirical results.

But in this post, I want to adopt a more philosophical approach: are there in principle things that shouldn’t be learnable from language alone? And could we ever hope to test for the absence of such qualities in text-based language models?

The limits of language-based assessments

I’ll start with the latter question.

First, let’s clarify what assessing a text-only language model actually involves: the researcher presents that model with a string of text (which is subsequently tokenized) and measures the model’s output. That output is itself a probability distribution over subsequent tokens; or, for more complex tasks, it’s another string produced by actually sampling from that probability distribution. The import of those probabilities or generated strings depends, of course, on the theoretical scaffolding behind the assessment. Concretely, though, we feed language in and get language out.

It’s possible that a methodological conundrum is already clear to many readers. Assessing a text-only language model’s ability to do X requires formulating “X” in linguistic terms.3 For instance, measuring a model’s “reasoning” ability requires writing a number of word problems and asking the model to produce a response (e.g., in the form of selecting the most likely answer—also written in language). Similarly, assessing the “Theory of Mind” of a text-only language model requires writing various scenarios meant to stand in for plausible real-world situations, and (again) asking the language model to produce a verbal response of some kind. (This is roughly what we did in a 2023 paper.) In order to produce these assessments, researchers must by definition assume that “X” can in some sense be expressed in language.

For many tasks and capacities, this isn’t necessarily a problem. But it does mean that claims about concepts or abilities that are thought to be ineffable—i.e., things that cannot be described in language—are practically impossible to assess in a text-based model. Assessing them requires formulating them linguistically somehow, which, if the concept is truly ineffable, should be impossible. If it is possible to formulate the concept as a string of linguistic symbols, that alone suggests that a model could be trained on those linguistic symbols and perhaps even learn to produce them in appropriate contexts.

Put another way: if a territory can be mapped linguistically, then it seems intuitively plausible that a language model could learn the map without knowing the territory; this renders it nigh-impossible to measure whether that model has, in fact, learned the territory.4

To clarify: I’m not implying here that we should assess a text-based model’s ability to do things that are clearly not linguistic, like pick up a cup of coffee. This would be absurd on its face, like asking people how high they can levitate5. My point, rather, is that it’s actually very hard to assess the limits of language as a training signal when language is the only assessment tool you have.

What about intermediate representations?

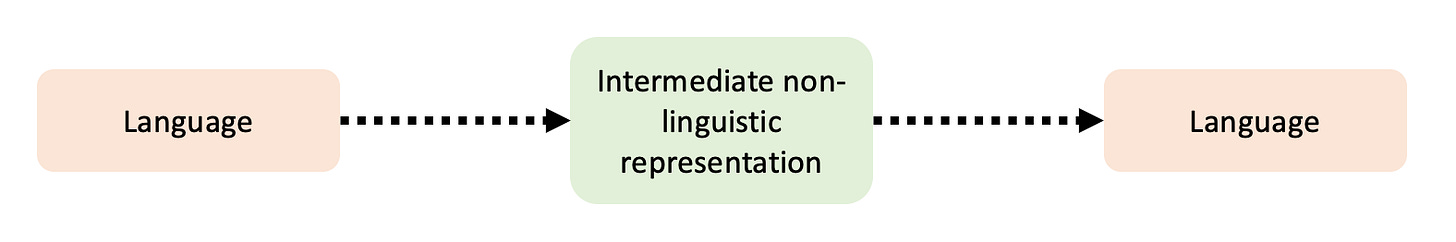

One healthy response to this problem might be to try to find exceptions. Are there cases where producing the right linguistic output for a given linguistic input depends on some kind of non-linguistic knowledge?

For instance, the theory of embodied simulation posits that understanding language involves “simulating” the sensorimotor details of the scenes that language describes. According to this theory, reading and understanding a sentence like “Sam kicked the ball” should recruit some of the same neural circuits involved in perceiving such an action or even executing that action yourself. The idea that meaning is intimately connected to grounded experience is an old one, with physician Carl Wernicke writing in 1874:

The concept of the word “bell,” for example, is formed by the associated memory images of visual, tactual and auditory perceptions. These memory images represent the essential characteristic features of the object, bell.

A more modern summary can be found in Ben Bergen’s 2015 chapter on the topic:

In other words, the same neural tissue that people use to perceive in a particular modality or to move particular effectors would also be used in moments not of perception or action but of conception, including language use.

If this hypothesis is correct, then simulation in some sense constitutive of language understanding. To be clear, the debate is by no means settled: as I’ve written before, there’s good evidence that simulation happens, but the evidence that it plays a necessary, functional role in comprehension is more muddled. Testing this is very hard (which is part of why it’s an unsettled debate), but the claim is clear: understanding language involves some kind of non-linguistic intermediate representation (sensorimotor representations), and thus in theory, producing the “right” responses to certain linguistic inputs should depend on whether the right intermediate representations are activated.

Here, the solution might seem straightforward: researchers should design tasks that putatively involve these sensorimotor representations and present them to language models. If text-based language models solve the task, it falsifies the hypothesis that the task depends on those sensorimotor representations; if they don’t solve it, it’s consistent with (though of course does not prove) the idea that the distributional statistics of language are insufficient to account for what people are doing when they engage in the task.

The challenge is actually identifying such a task!

The empirical question is one thing: thus far, language models have done surprisingly well on many tasks that seem like they should depend on some kind of world knowledge, suggesting they could pick up at least the simulacrum of that knowledge from text alone.

But lately, it’s the in principle side of the problem that gets me. This is where we return to the philosophical challenge raised in the previous section. If a task can be well-specified in terms of linguistic input and linguistic output, it’s not clear to me why there shouldn’t exist some solution to that task that can be implemented through representations formed by training on linguistic symbols. Such a solution might be what researchers sometimes call a “shortcut”—i.e., implying it’s not the “real thing”—but the behavior would be indistinguishable from what the “real thing” looks like.

In the limit, we could imagine that solution to be stored in some kind of “lookup table”, as philosopher Ned Block suggested in his famous “Blockhead” thought experiment; alternatively, perhaps it’s a large list of rules specifying the “correct” output in response to each input, as John Searle proposed in the “Chinese Room” thought experiment. Central to both these thought experiments is that we have to accept the premise that the system in question can produce behavior that’s indistinguishable from what you should expect from the correct solution—even though the system is by definition not using that solution. There is, after all, more than one way to peel an orange.

Assuming these scenarios are at least conceivable, we face the same problem I described earlier: probing the limits of language with linguistically-specified tasks is very hard (if not impossible).

At this point, empirically-minded readers might be tempted to construct modifications to the original task—what’s sometimes called adversarial testing. And in general, I think this is exactly the right approach: in the empirical world of evaluation and inference-making, researchers should absolutely subject a system to various stress tests (Natalie Shapira and others did this very effectively in a 2024 paper evaluating performance on various Theory of Mind tasks). I plan to keep doing this, and other researchers should too!

But philosophically, I think in principle concerns I’ve raised still stand, which I’ll summarize again here in bullet-point form:

Designing a task for text-based language models requires specifying linguistic input and linguistic output of some kind.

In order for such a task to be face-valid, the construct in question must in some sense be operationalizable in terms of language: the task should be linguistically expressible.

If the task is linguistically expressible, it’s possible to imagine that the representations required to solve that task could be learned from linguistic data alone—even if that solution isn’t the same as the one used by humans.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure there’s anything we can really do about this, and I still think rigorous, adversarial empirical testing is very important. But researchers should take care to acknowledge (and ideally investigate) the multiplicity of solutions a system might use to address a task; uncertainty is baked into the system, and we can’t avoid it.

We might also take this opportunity, however, to reflect on what kinds of representations, knowledge, and capacities we can’t assess using linguistic input and output: the truly ineffable. Not for the purpose of evaluating text-based language models—I don’t really think that makes sense, as I noted earlier—but for highlighting the rich varieties of human experience.

Ineffability and the limits of language

Some forms of experience seem to resist verbal expression. In a 2014 paper, cognitive scientists Steven Levinson and Asifa Majid defined ineffability as the “difficulty or impossibility of putting certain experiences into words” (pg. 2). As they point out in the paper, the debate about what (if anything) qualifies as “ineffable” is a longstanding one. Some philosophers (like Searle) argue that there’s no in principle bound on the expressibility of language, and that if something can be thought, then it can be spoken; similar arguments have been made about translating between languages (e.g., Donald Davidson has denied that there are mutually untranslatable languages).

Yet it also seems intuitively true that some domains of experience, and certain kinds of experiences within those domains, are more amenable to linguistic description than others. Most of us see human faces every day—we might even be biologically tuned towards recognizing faces6—but actually describing a face is very difficult. I, for one, have never read a description of a face that really fits, unless that description is something like: “They look exactly like [person you already know]”. This is in striking contrast to other visual percepts, like shapes or colors, for which we have a well-defined lexicon for a regular cast of recurring characters.7

More broadly, some sensory domains (like vision) are sometimes argued to be more ineffable than others (like smell or taste). Here, the actual empirical evidence is mixed: in languages like English, visual percepts are indeed more codable than olfactory ones, i.e., speakers more reliably use the same word to communicate about the same visual referent than the same odor; but in hunter-gatherer communities like the Jahai, odor is just as codable as vision, suggesting that olfaction is not in principle ineffable—it’s just not as expressible in many WEIRD languages.

Ineffability is also thought to be a hallmark of mystical experiences. In Varieties of Religious Experience, psychologist William James famously enumerated four such markers, including ineffability (it can’t be expressed in words), noesis (it feels clearly and obviously true), transience (it doesn’t last forever), and passivity (the subject does not control the experience). James writes:

The handiest of the marks by which I classify a state of mind as mystical is negative. The subject of it immediately says that it defies expression, that no adequate report of its contents can be given in words. It follows from this that its quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others. (Pg. 380).

James marshals a number of sources in support of this claim, including first-hand reports from people with mystical experiences. In some cases these experiences are brought on by a sense of the sublime (e.g., in a natural landscape or religious setting), and in others they are brought on by psychoactive drugs. Of nitrous oxide in particular, James writes:

Depth beyond depth of truth seems revealed to the inhaler. This truth fades out, however, or escapes, at the moment of coming to; and if any words remain over in which it seemed to clothe itself, they prove to be the veriest nonsense. Nevertheless, the sense of a profound meaning having been there persists… (Pg. 387)

Here, we see two of the key signatures of the mystical: the experiencer simultaneously feels that they cannot convey what they’ve learned (any words that come to mind “prove to be the veriest nonsense”), and yet cannot dispel the certainty that they have experienced something true and profound.

A final example of the ineffable is physical pain. One of the best-known philosophical treatments of pain can be found in Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain, a tour de force that includes topics such as political torture, the writings of Karl Marx, and tort law. In the Introduction, Scarry argues that physical pain is in some sense inexpressible and deeply unknowable by anyone other than the experiencer of that pain:

Thus when one speaks about “one’s own physical pain” and about “another person’s physical pain”, one might almost appear to be speaking about two wholly distinct orders of events. For the person whose pain it is, it is “effortlessly” grasped (that is, even with the most heroic effort it cannot not be grasped); while for the person outside the sufferer’s body, what is “effortless” is not grasping it (it is easy to remain wholly unaware of its existence; even with effort, one may remain in doubt about its existence or may retain the astonishing freedom of denying its existence; and finally, if with the best effort of sustained attention one successfully apprehends it, the aversiveness of the “it” one apprehends will only be a shadowy fraction of the actual “it”). (Pg. 4)

She continues, emphasizing in particular the notion that pain cannot be reliably shared through language:

Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it, bringing about an immediate reversion to a state anterior to language, to the sounds and cries a human being makes before language is learned. (Pg. 4)

Scarry argues—here, and throughout the book—that a “great deal is at stake” in the search to find some linguistic formulation that succeeds in accommodating the experience of pain. The consequences of this kind of project are practical, ethical, and deeply political.

She highlights the attempts of various groups to give voice to pain, from medical practitioners to Amnesty International. A particularly interesting and influential attempt can be found in the work of Ronald Melzack, who (among other accomplishments) helped develop the extensive McGill Pain Questionnaire. The questionnaire was a response to the noted inadequacies of existing medical approaches towards pain (“Rate your pain on a scale from 1-10”): in addition to the intensity of pain, the questionnaire asks patients to select specific words that convey the quality of the pain. The insight here was that certain clusters of words actually carry some amount of reliable information about the cause or nature of a patient’s suffering:

When heard in isolation, any one adjective such as “throbbing pain” or “burning pain” may appear to convey very little precise information beyond the general fact that the speaker is in distress. But when “throbbing” is placed in the company of certain other commonly occurring words (“flickering”, “quivering”, “pulsing”, “throbbing”, and “beating”), it is clear that all five of them express, with varying degrees of intensity, a rhythmic on-off sensation, and thus it is also clear that one coherent dimension of the felt-experience of pain is this “temporal dimension”. (Pg. 7)

Does the fact that different qualities of pain can be associated with different lexical content disprove Scarry’s initial claim that pain resists verbal expression? I don’t think so: as Scarry points out, it’s not as though Melzack’s questionnaire solves the ineffability of pain—it’s simply a valiant attempt by a doctor to give suffering patients a voice (and in the process, hopefully aid in the diagnostic process). Perhaps the best we can hope for is a partial and very lossy map for the vast, subterranean territory of pain, and even with such a map others will “retain the astonishing freedom of denying its existence” (pg. 4).

Addendum

This is all, of course, rather far afield from where we began: the question of whether there are certain domains that we should expect text-based language models to fail to learn in principle.

My central claim in the first half of this essay was that if a domain is in some way amenable to verbal expression—a prerequisite to designing a task with linguistic input and output—then a text-based language model should be in principle capable of mapping that domain to solve a linguistically formulated task. That doesn’t entail, of course, that text-based language models will do this, and it certainly doesn’t entail that any solution they’ve happened upon is the solution humans use for this task (I call this differential construct validity). In the limit, one could imagine a language model trained on the exact input/output pairs for a given task and simply regurgitating them from memory. Such a solution would be very uninteresting but it might, unfortunately, be behaviorally indistinguishable from the “right” solution.8

This methodological conundrum could be discouraging to some, and indeed, there is something deeply frustrating about it. Yet as I’ve argued in the second half of the essay, I think it could also represent an opportunity to reflect on the limits (if any) of language as a vehicle for conveying the rich textures of experience. I am a writer, so naturally I think quite highly of language. But even I must admit that there is much in the character of experience that resists expression. Perhaps the methodological conundrum I’ve highlighted can help serve as a reminder that there is much more to life than what can be captured in a language-based benchmark.

I’ll be focusing explicitly in this post on language-only models, i.e., not vision-language models or other multimodal models.

Or, alternatively, proponents of more explicit symbolic models, like Gary Marcus and others. This post doesn’t really engage with questions about structured world models and whether and to what extent systems like LLMs have them—my focus is more on the role of experience in forming knowledge about the world.

More generously, we might say “in terms of a tokenizable string”.

This also takes us into strange metaphysical waters, ie, is there in fact a territory apart from the map, ontologically and/or epistemically?

Though I do think it’s worth noting the many things that a language model trained on text alone cannot do, lest we lose sight of the fact that humans do exist in situated environments and (for now) do not merely move cursors on a computer screen.

Another matter of intense debate, to be clear!

It’s worth noting, of course, that there are many irregular shapes or in-between colors for which people might struggle to find an appropriate label.

Though not, perhaps, if one subjected the model to more rigorous adversarial testing or attempted to identify the mechanistic underpinnings of that solution.

I loved this! The Scarry passage reminded me of the Wittgenstein section about beetles in a box. As in people can describe their own respective beetles to each other but language can’t really get off the ground without people being able to compare their beetles and see the referents directly. And this seems to be a similar case for pain but also for other internal experiences like emotions. We can only point to/verify the conditions under which they occur, not the experiences themselves.

And it’s interesting to think that part of what makes things ineffable is not that it’s impossible to design words that vary with their features. But that we can’t establish common ground on the referent. I wonder whether that fundamentally changes what these words “mean” when LLMs produce them.