Evaluating empirical claims: practical advice

A conceptual framework for identifying the type and validity of empirical claims.

Claims about the world and its inhabitants abound, both in the scholarly literature and in public discourse. One of the most important things a person engaging with these claims can do is learn how to evaluate them, sometimes (though not always) with a critical eye.

I want to be clear about what I mean by this. I’m not endorsing here a kind of epistemic nihilism: I think most people are already aware, on some level, that at least some of the claims they encounter are misleading at best and false at worst—and unfortunately this leads, all too often, to a kind of reflexive disbelief that is often just as bad as its inverse. I’m also aware that most people simply do not have the time to investigate the epistemic foundations of every claim they encounter, which is precisely why networks of trust are so crucial to constructing knowledge.

What I am suggesting, rather, is as follows: first, if you come across a claim, it is useful to wonder what theoretical assumptions or empirical evidence that claim relies on; second, this process of “wondering” can be made much easier by using some kind of conceptual framework, which offers a defined lexicon for doing this kind of cognitive work. There are many such frameworks one could choose from (e.g., many perspectives from critical theory), but I’ll focus here on an approach commonly taught and used in Cognitive Science for evaluating empirical claims in particular.1 I originally taught this framework in a Research Methods course (using materials from Beth Morling’s excellent textbook on Research Methods in Psychology), but it’s gone on to inspire much of my current focus on the epistemological foundations of research on large language models (LLMs). Many people already implicitly adopt aspects of this framework, but individual critiques (or responses to critiques) can be made more precise by understanding it in more detail.

Fortunately, the framework itself is relatively simple and primarily consists of answering two questions:

First, what kind of claim is being made?

Second, is that claim valid?

Crucially, the validity of claims can be evaluated in multiple ways, and different kinds of validity are more or less important for different kinds of claims. That’s why it’s important to start by identifying the kind of claim in the first place.

What kind of claim is being made?

Oversimplifying a bit, there are roughly three types of empirical claims one could make: frequency claims, association claims, and causal claims.

A frequency claim is a claim about the rate or degree of something. For example, the assertion “4 in 10 people text while driving” is a claim about the rate (40%) of people putatively texting while driving. Another example would be “Human adults encounter an average of 100M words in their lifetime”. (Note that I’m not arguing either of these claims are true or false!) In both case, the claim is about a single variable (e.g., texting while driving or number of words encountered), and expresses some descriptive statistic about that variable (e.g., the rate or average2).

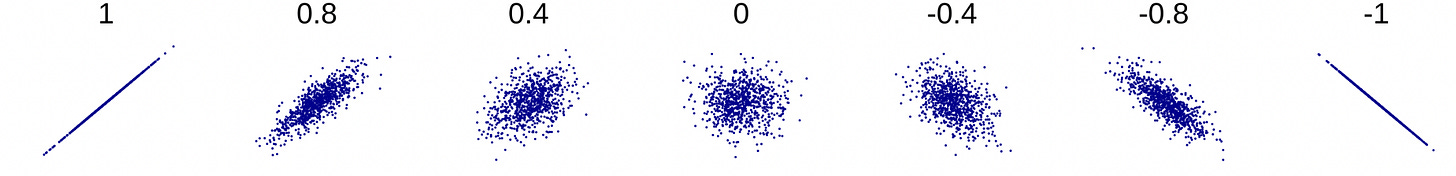

An association claim is (unsurprisingly) a claim about the direction and strength of association between two or more variables. With continuous variables, the direction of association is most intuitively illustrated using something like a scatterplot. For instance, two variables might be positively associated (as X increases, so does Y), negatively associated (as X increases, Y decreases), or not associated (Y is unrelated to changes in X). The strength of association refers to something like the extent to which values of Y can be reliably estimated from values of X. Both these dimensions of associational claims are depicted (along with an associated Pearson’s correlation) in the figure below, ranging from a perfectly linear positive correlation to a perfectly linear negative correlation.

Of course, associations can be non-linear as well. That same image from Wikipedia includes visual examples of relationships that seem clearly structured but correspond to a correlation of 0: a good example (along with Anscombe’s Quartet) of the perils of relying on statistics without plotting your data.

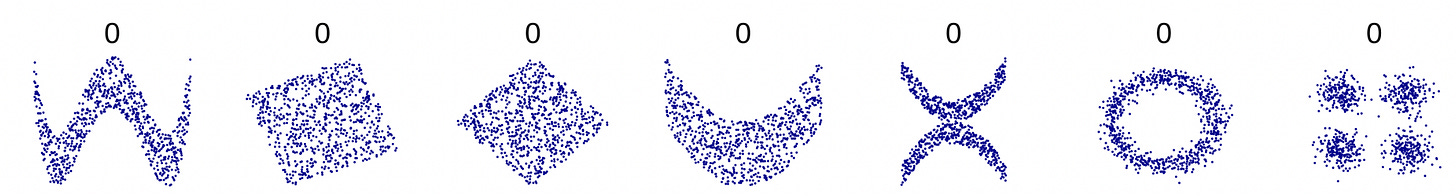

So far, my definition of associational claims has been rather abstract. But you likely encounter associational claims all the time: anytime two or more variables are described as being related to each other (though not necessarily in a causal relation), that’s an associational claim. For example, Our World in Data contains a scatterplot showing the relationship between GDP per capita and self-reported life satisfaction, depicted below.

Judging by eye, this relationship seems positive and of moderate strength. Someone might assert something like: “Countries with higher GDP per capita also have a higher average self-reported life satisfaction.” We could also put this in terms of prediction: “A person from a country with a higher GDP per capita is likely to have a higher average self-reported life satisfaction.”

Note that these statements make no claims about whether this relationship is causal (nor in which direction). It could very well be that residing in a country with higher GDP per capita makes people more satisfied with their lives—indeed, this empirical evidence could be consistent with such a claim. But the evidence is also consistent with the inverse claim (i.e., that higher life satisfaction leads to higher GDP per capita), and it’s also entirely possible that the relationship is spurious or dependent on some hidden confound. We’re also, for now, not assessing the validity of the claim: we’re just describing what kind of claim it is.

A causal claim, in contrast, does claim that one or more variables is somehow causally responsible for changing some other variable(s). Such claims are often (though not always) accompanied by certain verbs expressing a causal relationship, such as “affects” or “changes”.3 For example, the claim “Taking music lessons improves pitch perception” is a causal claim about the efficacy of music lessons. Interestingly, it does contain within it a kind of association claim: presumably, people who take music lessons scored more highly on some measure of pitch perception than people who didn’t. But the expression of a causal relationship between these variables assumes that something about our design or collection of the data justifies the stronger, causal claim: for example, perhaps participants were randomly assigned to take music lessons vs. some control condition.

Association and causation are often conflated—so often that many readers will likely have encountered the mantra “Correlation does not imply causation”. There’s a rich philosophical literature on the nature of causality and when, epistemologically, we are justified in drawing causal inferences; I won’t go into too much detail here, but I do discuss specific inferential issues (like internal validity) below. Suffice to say: first, the issue is complicated; second, random assignment is generally viewed as the “gold standard” for establishing causality; but third, there are various other data collection and statistical modeling techniques for trying to establish causation when random assignment is impossible or unethical. These techniques (like regression discontinuity design, the use of instrumental variables, etc.) are common in fields like Econometrics or Epidemiology, where researchers tend to rely on observational data rather than controlled experiments.

Having established the kind of claim being made, we can turn to identifying whether that claim is valid.

The four validities

There are (at least) four ways in which a claim’s validity can be assessed: construct validity, external validity, statistical validity, and internal validity.

Construct validity

Construct validity refers to how well a variable is operationalized. As I’ve written before, many variables of interest in Cognitive Science (and throughout much of science!) are relatively abstract, and cannot be measured “by eye”. Instead, they require some kind of instrument to measure them, hopefully with some degree of reliability and precision. Even something that seems as concrete as temperature requires specific instruments for measuring the variable; and as Hasok Chang describes in Inventing Temperature, the historical path towards building and refining these instruments often consists of considerable trial-and-error. Variables like “life satisfaction” or “Theory of Mind” are even more fraught: researchers may not even agree on the correct definition of the variables in the first place, much less how to measure the variable—indeed, some might even argue that the construct cannot be measured in any useful or reliable way.

Most readers have probably encountered critiques of construct validity before. It’s an especially common argument in the discourse on the “capabilities” of Large Language Models (LLMs): namely, that the performance of an LLM on some “benchmark” designed to assess some ability does not reflect the actual capacity in question, but rather some “shortcut” or “cheap trick” that produces indistinguishable behavior. Adjudicating between these possibilities requires identifying potential “shortcuts” a system (or human!) might be using and perhaps designing an evaluation that removes the possibility of using such shortcuts: in short, doing the hard theoretical and empirical work of validating an instrument.

It’s also common when discussing variables such as “happiness” or “life satisfaction”, which some view as the kind of variable that inherently resists quantification. Take, for example, the scatterplot we saw earlier showing a positive relationship between GDP per capita and self-reported life satisfaction. The associational claim that “Wealthier countries contain happier people” could be critiqued on grounds of construct validity: namely, someone might argue that self-reported life satisfaction is not a good measure of “actual” happiness. In response, someone who does think that it’s a good measure would need to defend the construct validity of the claim.

Establishing the validity of an instrument depends on several factors. The instrument should ideally be reliable (i.e., it produces consistent results), face valid (i.e., it seems theoretically and intuitively plausible as a measure of the construct), and exhibit both convergent and predictive validity (empirical measures of the extent to which the measure correlates with other measures of the same construct). Readers interested in this topic might enjoy my previous post describing the process of establishing construct validity in more detail.

External validity

External validity refers to how well a given claim generalizes to the population of interest.

This is another topic I’ve written about extensively, both in the context of studying human cognition and studying systems like LLMs. In each case, researchers are typically interested in drawing conclusions about some “population of interest” (e.g., human cognition). But researchers can’t, of course, study every human that’s ever existed, so they make do with a sample. If the sample is random and representative of the underlying population, then facts about the sample can sometimes be generalized to the population. However, if the sample is not representative (as is the case with so-called “WEIRD” psychology), then drawing these generalizations is unjustified.

External validity is also at the heart of recent debates about the validity and utility of political polling. The point of a poll is to produce an estimate of the current degree of support for particular candidates or ballot measures. Unlike a census, polls are generally conducted on a sample—not the entire population. Typically, researchers will conduct a large-scale surveys of their intended population (e.g., citizens of the United States) and extrapolating from the results of such a survey to their population of interest.

A key problem in this approach is selection bias: if some people are systematically more likely to respond to a poll than others, and if this systematicity is correlated with what the poll is measuring (e.g., support for Democratic vs. Republican candidates), then the poll’s results might be biased. Here, “bias” has a specific technical definition: namely, that an “estimator” (e.g., a statistic calculated on a sample) will systematically misestimate the underlying parameter of interest. While all sample statistics will be a bit wrong (because of sampling error), an unbiased estimator is one that is equally likely to overestimate or underestimate the true value—bias, on the other hand, is more problematic because it causes researchers to make systematic errors in judgment.

Establishing external validity is also complicated! It depends, at minimum, on two factors: first, a coherent definition of the “population of interest”; and second, a method for reliably producing representative samples of the population (such as random sampling). In some cases, researchers also try to use more sophisticated statistical approaches to counteract potential selection biases: for example, pollsters sometimes factor the state of the economy or previous voting patterns in a region into their estimates.

Statistical validity

Statistical validity refers to whether a given conclusion about the data is justified or reasonable on the basis of the statistical evidence presented.

As I’ve discussed before, scientists rely on various statistical techniques for modeling their data and testing hypotheses about the relationships between variables. The valid use of these techniques depends, in turn, on various assumptions. For instance, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression assumes that each observation is independent; violation of this assumption can artificially decrease the standard error estimates in an OLS model, increasing the probability of a false positive error. This is why researchers studying datasets with non-independent observations now rely on more sophisticated techniques that explicitly account for these sources of non-independence, such as mixed effects models.

In general, drawing conclusions from statistical analyses depends on all sorts of assumptions, which aren’t always met. Issues like insufficient statistical power and multiple comparisons without correction are other examples of practices that could in principle jeopardize statistical validity. When an analysis is not statistically valid, the chance that some kind of inferential error is made increases: whether that error is a false positive or a false negative depends on the nature of the statistical mistake.

My sense is that, in part due to consequences of the replication crisis, researchers have become more aware of statistical validity as a concern. At the same time, statistical modeling techniques are not always taught in sufficient detail for researchers to be able to recognize these issues when they arise.

Internal validity

Internal validity refers to how successfully a piece of evidence supports a causal claim.

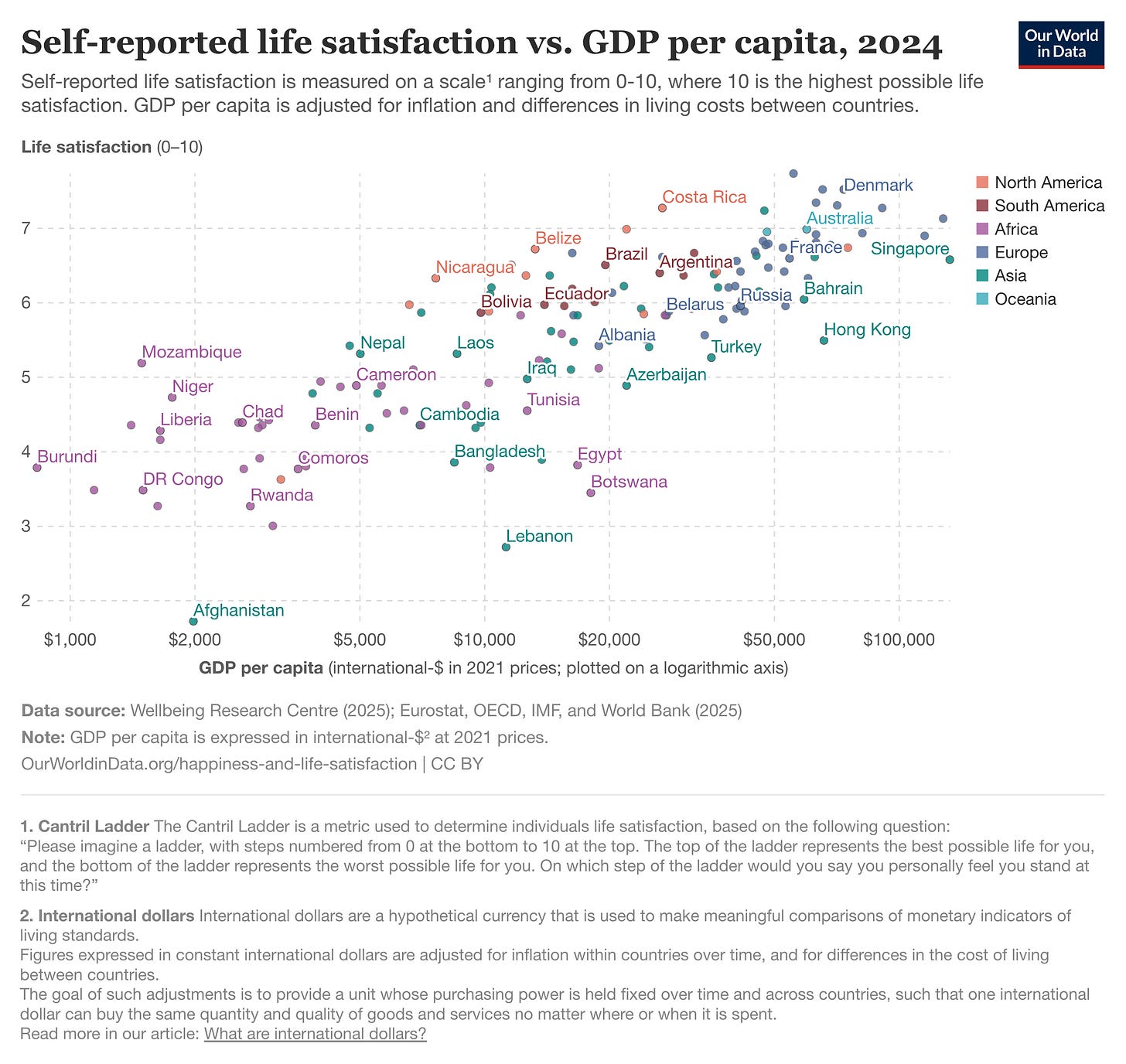

While causal inference is by no means a settled issue, researchers tend to agree that causal claims like “A causes B” require that at least three criteria be met: temporal precedence (A comes before B); association4 (A is related to B); and the elimination of confounds (i.e., accounting for alternative causal pathways for B). The phrase “internal validity” typically refers to that last criterion (eliminating confounds), though I’ve sometimes seen it used to refer to all three.

A confound is simply a variable that affects both the outcome variable (B) and the explanatory variable of interest (A). If some confound C causes changes in both A and B, it is plausible that A and B will be correlated even if they are causally unrelated. Crucially, if we fail to account for C—either in our experimental design or in our statistical analysis—we might infer that A and B are in fact causally related.5

An example that’s often taught in introductory statistics classes is the positive correlation between the number of ice cream sales in coastal towns and the number of shark attacks in those same towns. There is, in some datasets, a genuinely significant and positive relationship here: that is, knowing the number of ice cream sales gives you some ability to predict the number of shark attacks—better than knowing nothing, at any rate. But this relationship clearly makes no sense from a causal perspective: how exactly could people buying more ice cream lead to more shark attacks (or vice versa)? The hidden confound, of course, is temperature: people are more likely to buy ice cream in hotter weather, and they’re also more likely to swim in the ocean, increasing the chance of a shark attack.

How, then, do researchers eliminate confounds?

The gold standard, as I mentioned above, is the use of experiments with random assignment: that is, participants are first randomly assigned to one of multiple experimental conditions (say, Treatment vs. Control); then, some intervention is applied; and finally, outcomes are compared across conditions. The core intuition here is that if participants are equally likely to have been assigned to the Treatment vs. Control condition—since the assignment is purely random—we are in some sense “automatically” accounting for any differences in the sample of Treatment participants and the sample of Control participants.

Random assignment helps address confounds arising from pre-existing variation in the participant population. But researchers must also eliminate potential confounds in the design of their experimental conditions as well—i.e., differences in the stimuli or procedures that participants are exposed to other than the primary experimental contrast of interest. For instance, suppose a researcher is interested in whether people respond faster to more frequent words than less frequent words. If they don’t account for the empirical fact that frequent words also tend to be shorter (Zipf’s law of abbreviation), they might incorrectly attribute a treatment effect to word frequency rather than word length. These confounds are typically best addressed through careful experimental design (e.g., matching stimuli for length across conditions).6

Which kind of validity matters most?

A natural question to ask at this point is whether one of these four validities is particularly crucial and perhaps worth devoting special attention to.

The answer is that it really depends on the nature of the claim being made. Internal validity is very important for causal claims, in which a causal link is expressed between two or more variables (“A causes B”); in such cases, it is critical that researchers do their best to eliminate alternative explanations (e.g., “C causes both A and B”). On the other hand, for frequency claims (e.g., “The average A is 4.5”), the notion of a confound is much less relevant, so internal validity never really surfaces as an issue. The same could in principle be said of association claims, since a true association claim does not express a causal link—the only caveat is that some putatively associational claims are actually causal claims, so readers should be careful to identify whether someone has snuck causal language in somewhere.

External validity, on the other hand, is key for frequency claims. Descriptive statistics (e.g., the average height of California residents; or the number of people who text while driving) don’t generally grant anything like mechanistic insight; instead, their primary utility is summarizing some property of a population. Here, it really matters that the sample is representative of the population of interest. In contrast, while external validity does matter for causal claims—this is a central critique of laboratory experiments—there’s still considerable merit in demonstrating a causal link even in the absence of a representative sample; as psychologist Paul Bloom pointed out in a recent post, such work can provide mechanistic insights about how some system behaves under controlled conditions.

Statistical validity is relevant to some degree for all types of claims: it always matters that one’s conclusions rest on solid statistical principles. In my experience, however, issues with statistical validity are more likely to arise with claims about association or causation, since those claims rely on more complicated statistical techniques that quantify the relationship between two or more variables, and it’s easier to make mistakes in the execution or interpretation of these techniques. Of course, that doesn’t mean researchers can’t make statistical errors with frequency claims—an example would be conflating the mean and median of a distribution.7

Construct validity, as I’ve argued before, is perhaps the most omnipresent form of validity. Any kind of claim is vulnerable to a criticism about how the constructs have been operationalized. For instance, the frequency claim “4 in 10 people text while driving” hinges on how exactly this estimate has been produced. Did survey respondents self-report whether they ever texted while driving? Did researchers install cameras on street corners and annotate how often individuals texted while driving? Similarly, the association claim “Wealthier countries contain happier people” relies on an appropriate operationalization of both wealth and happiness. And while no metric is perfect, we might be more confident about any given metric (e.g., self-reported life satisfaction) if it’s been shown in independent studies to correlate with other measures of the construct (i.e., it demonstrates convergent validity). Finally, causal claims are effectively association claims with a causal link, so construct validity applies there as well. As with external validity, some researchers might (fairly) argue that it’s worth sacrificing some construct validity to demonstrate a causal link. Such an argument is entirely reasonable—but it’s also why, as I’ve argued before, it’s important to pair such controlled studies with observational studies that sacrifice internal validity for improved construct and external validity.

Putting the framework to use

I write frequently about Large Language Models (LLMs), with an emphasis on how we might try to reliably learn things about them. As such, I encounter claims about LLMs quite often—as I’m sure many readers of this newsletter do. Having established the kinds of empirical claims and the four validities with which to evaluate them, we can now apply this conceptual framework to claims about LLMs.

Consider the following hypothetical claims:

The average hallucination rate of frontier LLMs is 20%.

The size of a model is positive correlated with reasoning performance.

Chain-of-thought prompting improves reasoning performance.

In evaluating each claim, we might first identify what type of claim it is. (1) appears to be a frequency claim: it is a summary statistic (the average hallucination rate) about some population (frontier LLMs). (2) appears to be an association claim: it expresses a relationship (a positive correlation) between two variables (model size and reasoning performance). And (3) appears to be a causal claim: it expresses a causal link (“improves”) between two variables (chain-of-thought prompting and reasoning performance).

We can now interrogate the validity of each claim. Let’s start with (1), which we already established was a frequency claim. There are two crucial dimensions to notice here: first, the variable being summarized (hallucination rate); and second, the population of interest (frontier LLMs). The question of how hallucination rates were assessed is a question of construct validity—how confident can we be that the evaluation used is both reliable and a valid predictor of hallucination rates “in the wild”? The question of which LLMs were studied is a question of external validity—what exactly is meant by “frontier LLMs”, and which specific LLMs were studied in the context of this study? Are those specific LLMs representative of the population being described?

We can ask similar questions of (2), which is a claim about association: larger models display better reasoning performance. Construct validity applies now to two variables instead of one. Model size is typically measured in terms of the number of parameters (weights) in the model, but we’d want to make sure that’s what the metric refers to in this particular context. Reasoning performance is much more abstract and presumably relies on specific reasoning benchmarks; whether or not we think those benchmarks are actually reflective of true reasoning capacity presumably depends both on our a priori theoretical perspective (whether we think LLMs are capable of reasoning) and empirical facts about the benchmarks themselves (e.g., whether they correlate with other indices of reasoning). In this case, external validity refers (again) to the sample of LLMs tested. This is relevant to knowing whether the positive correlation observed is likely to be true across the board, or whether it applies only to a subset of LLMs: is it always the case that larger LLMs will perform better on these tasks? Finally, statistical validity is relevant here: how exactly was the positive correlation calculated, and how strong is the measured association?

(3) is a claim about a causal link between two variables: chain-of-thought prompting (in which a model is instructed to think through a solution step-by-step) and reasoning performance. As with (2), the same construct validity questions about reasoning performance apply: how confident should we be that the evaluations assess reasoning in particular as opposed to some other latent variable? Are we primarily assessing a certain kind of reasoning (E.g., mathematical reasoning or analogical reasoning) or are we making a claim about reasoning “in general”? We might also (again) be concerned about external validity: which LLMs were assessed to make this claim? We will be more confident about the generalizability of the result if we observe a similar effect across 100 LLMs than if we tested only a single model. Finally, because this is a causal claim, we also care about internal validity. To make a claim like this, researchers would probably conduct an experiment in which models were prompted either with chain-of-thought prompting or with some “control” condition—but the validity of such a causal claim depends on the researchers successfully eliminating all differences between conditions except for the experimental manipulation. Even something as seemingly trivial as the length of the prompt might matter, so it could be helpful to include multiple control conditions, which account for different potentially confounding factors.

There’s also a fourth kind of claim about LLMs that might be even more common: that is, claims about the performance of a specific LLM, such as “GPT-4 passes the bar exam”. In terms of the framework I’ve described here, these are clearly not association claims or causal claims, but it’s also not clear that they’re intended as frequency claims about a population of LLMs; if they are frequency claims, they’re claims with very poor external validity, given that only a single model was assessed. In some ways, they’re arguably closer to something like a “case study” or perhaps an “existence proof” for some phenomenon. The key validity to focus on, then, is probably construct validity: what instrument was used to assess the performance of the model, and how reliable and valid is this instrument as an operationalization of the underlying construct people might be interested in?

Crucially, none of these questions about any of the claims we’ve considered here can be answered without knowing more details about how each claim was actually produced. A good research paper should ideally provide all the details necessary to answer such questions, but in some cases, answering them will be impossible. A failure to answer such questions is not a failure on the part of the reader; indeed, this kind of uncertainty is itself useful information for deciding how much credence to assign to a given claim. For example, if it’s not clear how the researchers in a study assessed “reasoning performance”, then any claims about the reasoning performance of LLMs—or the variables that affect reasoning performance—should be taken with a fairly large grain of salt.

My hope is that equipping readers with this conceptual framework—three kinds of claims, and four validities with which to assess them—can help them navigate the epistemic landscape. In turn, the people producing claims might consider consulting a framework like this to help make their epistemic contributions more precise.

Related articles:

There are other kinds of claims one could make that don’t depend on empirical evidence, such as definitional claims.

Frequency claims could, of course, reference other descriptive statistics as well, such as the median or even a measure of the variance of a variable.

Note, too, that the presence of hedging (“may change”) does not change the kind of the claim being made—just the speaker’s epistemic stance towards the claim.

Note that the absence of a significant association between two variables does not imply no causal relationship. There are all sorts of reasons why a real causal relationship could be masked such that one would fail to detect an association.

Confounds don’t always produce false positives; in some cases, failing to account for a hidden cause can actually mask a real association between A and B, producing a false negative.

If the design does not address these issues, researchers can attempt to address them after the fact in their statistical analysis (e.g., including word length as a covariate). This introduces problems of its own and is sometimes misinterpreted as “controlling for” an effect, when it is in fact adjusting for some covariate in a way that may not always eliminate actual confounding.

This is most relevant with skewed distributions or distributions with very extreme outliers. The presence of skew or outliers affects the mean more than the median, but these summary statistics are often conflated.